Roundabouts are bad but they don't have to be

Roundabouts can no longer be called a new idea, even in North America they’ve existed for decades now. But while Traffic Engineers touted this new traffic control device from Europe as a solution to many of our road safety issues, they are widely and rightly panned by pedestrian and cycling advocates.

Yet in the Netherlands, where I now live, traffic circles usually aren’t anti-pedestrian or anti-cyclist. So what is the difference? I hear two main complaints issued against the design of roundabouts in North America.

Crosswalk Location

Many people will argue that the crosswalks need to be further from the intersection. This is incorrect. The crosswalk should be 1-2 car lengths away from the traffic circle in order to give drivers a place to stop when exiting the circle out of the flow of traffic, but not blocking the crosswalk. 1-2 car lengths is exactly the right distance for this.

Putting crosswalks further away is harmful for a number of reasons. First, drivers accelerate away from the circle. This means the further the crosswalk is away from the circle the faster drivers are traveling when they reach it. Therefore the farther a crossing is from the circle, the more dangerous it is, because drivers will be traveling faster.

Second, it is an equity and a user experience issue. Pedestrians should not be required to walk a significant distance out of their way just to cross the road. But aside from being unfair, it is simply ineffective. If the crosswalk were located say 40 meters from an intersection, pedestrians simply wouldn’t use it. They would cross at the intersection, as is logical and fair, and yet, would be blamed for not crossing in the crosswalk when a collision occurs.

And this follows from practice. You can see in these two images below this plays out in practice—roundabouts in the Netherlands place crossings within 1-2 car lengths of the circle and a roundabout in Canada places them a little bit further, but within the same range.

Centre Islands

Another common explanation I hear for roundabouts poor record in North America is these darned centre islands. Objections explain “I can’t see the far side, so how can I safely navigate the circle. That stupid island is making it unsafe.”

And again, this is wrong. The centre island is in fact a safety feature, and one that is found on safer roundabouts in the Netherlands (often very ornately).

A driver approaching a roundabout has 5 tasks to complete. First, they look for pedestrians (or cyclists) crossing. Then they look for traffic from the left. Then they proceed through the circle, then they look for pedestrians or cyclists at their exit.

Notice that at no time, is a driver required to look at two things at once or required to look across the intersection. This is what makes roundabouts potentially very safe. They are much simpler traffic control devices than signalized intersections. For example, a driver turning left at a signalized intersection with an uncontrolled left (most intersections) will have to look for oncoming traffic at the same time as they look for pedestrians coming from behind them. No wonder they’re so dangerous.

Therefore, the island in the middle serves to obscure the drivers view of irrelevant information. A driver does not need to know if the crossing on the far side has pedestrians at it. They are not there yet. They need to be looking at the crossing on the near side and on traffic coming around the circle.

Speed

So, what does make Dutch roundabouts safer. Well the answer can be found by looking deeper into people’s objections to North American roundabouts. In both cases drivers will explain, well the crossings should be farther so that I have more time to react. And the island should be gone so that I can see the crossing earlier so that I can react sooner.

In both cases, the problem is that drivers are driving too fast. They cannot react in time to be safe. This is even recognized by traffic engineers in the Region of Waterloo. How did they respond? The same way they do every time speed is a problem. The wrong way.

Yes, Waterloo Region’s engineers, realizing their error, lowered the speed limit on this major 70km/h arterial road for just the duration of the roundabout. How many drivers do you think follow this speed limit (at least after the temporary police traffic enforcement activities were finished).

Dutch roundabouts on the other hand bake in speed restrictions from the start. In many cases the roundabouts have raised crossings. You can see this by the so called ‘piano keys’ approachign the crossing (those are the short and long lines just after the dotted yield line and just before the bike lane with the elephants feet, you can see the crosswalk markings in the distance).

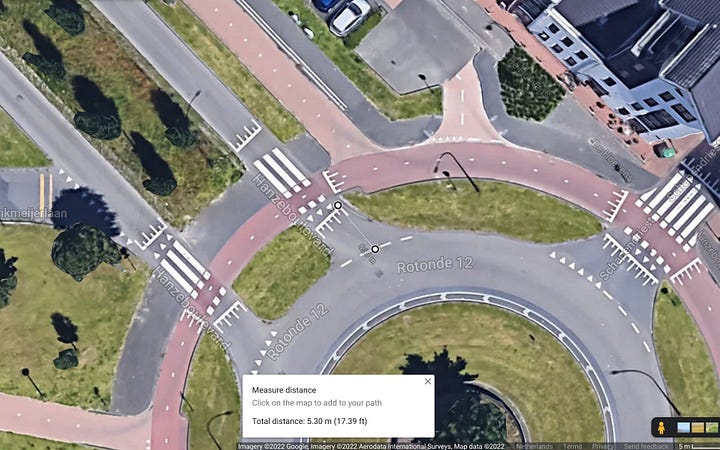

Entrances to the roundabouts are narrow with relatively sharp corners. You can see in the below image that in addition to the road itself being very narrow, the entrance to the roundabout actually narrows even further. This significantly reduces the crossing distance for pedestrians and cyclists but also forces drivers to slow to a very slow speed at the choke point.

And you can also compare with the roundabout on the left found in Kitchener, how wide and sweeping the entrances are. They are designed to encourage drivers to keep their speed up, and this is what makes the roundabout dangerous.

When it comes right down to it, this isn’t an accident. The goals of the designs are different. In the Dutch design safety and slow speeds are prioritized. Yes, drivers take longer to traverse this intersection, but that is a trade off that they are willing to make for safer intersections.

The Canadian and American designs prioritize throughput of fast motor vehicle traffic above safety and above pedestrian and cyclist accessibility. This is a systemic problem pervasive throughout the entire transportation engineering discipline. This is how it affects roundabouts. This isn’t unknown to engineers in North America. The goals of the transportation system must change.